TTABlog Quarterly Index: April - June 2006

Boy, was that a long quarter or what? Lots of citable cases, however, with the Board's total for the year reaching 34. Leo Stoller started the quarter like a lion but left like a lamb. We're still awaiting the Board's order regarding Stoller's infamous extension-request campaign. The Board's "show cause" letter sent in mid-April seems to have brought the program to a halt -- at least for now. And what ever happened to the Board's proposed rule changes? Let's hope the TTAB goes back to the drawing board with that proposal.

Section 2(a) - deceptiveness:

- TTAB Affirms Three Deceptiveness Refusals of "SWISSGOLD" for Watches and Parts

- TTAB Citable No. 20: Divided Panel Affirms 2(a) Deceptiveness Refusal of "CAFETERIA" for Non-Cafeterias

Section 2(a) - disparagement:

Section 2(d) - likelihood of confusion:

- TTAB Reverses 2(d) Refusal of "T1" For Flashlights, Finding Lighting Fixtures Not Related

- TTAB Finds "SOY2O" and "FRUIT2O" Not Confusingly Similar for Flavored Water

- TTAB Affirms 2(d) Refusal of "IN THE PINK," Finding Handbags and Clothing Store Services Related

- Yankees Win Again! CAFC Affirms TTAB "BABY BOMBERS" Decision

- World Cup 2006 Begins; TTAB Reverses 2(d) Refusal of "T2" for Flashlights

- CAFC Affirms TTAB Dismissal of "M2 COMMUNICATIONS" 2(d) Opposition

- Citable No. 29: TTAB Reverses "BOX SOLUTIONS" 2(d) Refusal, but Affirms Disclaimer Requirement of "SOLUTIONS"

- TTAB Affirms Another 2(d) Refusal: Appellants Batting .088 in 2006

- TTAB Finds "MAPCAD" and "CADMAP" Not Confusingly Similar, but Affirms Indefiniteness Refusal

- "WORLD GYM" Flexes Its Muscles in TTAB 2(d) Opposition Victory

- Citable No. 25: TTAB Attempts to Clarify Doctrine of Foreign Equivalents in Affirming 2(d) Refusal of "MARCHE NOIR"

- Citable No. 24: TTAB Dismisses 2(d) Cancellation Re "SUZLON & Design" for Wind Turbines

- TTAB Dismisses 2(d) Opposition: "UNCLE DUTCH" Not Confusingly Similar to "VON DUTCH"

- TTAB Reverses 2(d) Refusal of "PLAYER PRIVILEGES" for Casino Services

- In a Non-Precedential Ruling, CAFC Affirms TTAB's Uncitable "TORRE MUGA" Decision

Section 2(e)(1) - merely descriptive:

- Sarcasm Fails to Sway TTAB: Refusals of "ALLERGY WIPES" for Eyelid Wipes Affirmed

- TTAB Affirms Mere Descriptiveness Refusals of "THIRTYS" and "TREINTAS" for Wheel Rims

- TTAB Reverses Disclaimer Requirement of "TELECHAT" for Dating Services

- TTAB Affirms Disclaimer Requirement of "One Minute" for Bug Remover

- TTAB Reverses 2(e)(1) Mere Descriptiveness Refusal of "PATCH BOOSTER" for Heart Devices

Section 2(e)(1) - deceptively misdescriptive:

Section 2(e)(2) - primarily geographically descriptive:

- Citable No. 33: TTAB Affirms 2(e)(2) Refusal of "BAIKALSKAYA" as Geographically Descriptive of Vodka

- TTAB Okays "SWISSAIRE" Drawing But Affirms 2(e)(2) Refusal

Section 2(e)(3) - primarily geographically deceptively misdescriptive:

Section 2(e)(4) - primarily merely a surname:

Abandonment:

Disclaimer practice:

- TTAB Reverses Disclaimer Requirement of "TELECHAT" for Dating Services

- Citable No. 28: TTAB Reverses Disclaimer Requirement and Clarifies Unitary Disclaimer Rule

Filing basis:

- Citable No. 27: Domestic Assignee of Section 44 Applications Allowed to Amend Basis for Registration

Fraud:

- Citable No. 31: TTAB Sustains Opposition to Two Product Design Marks as Functional and Non-Distinctive, but Dismisses Fraud Claims

- TTABlog Recommended Reading: a New TMR Article on Fraud

- The TTABlog Fraud Collection: Is There a Fraud in Your Future?

- Citable No. 19: TTAB Rejects Fraud Claims, Grants 2(d) Cancellation Counterclaim

Functionality:

- Citable No. 34: TTAB Affirms Refusal of Flavor as a Mark for Pills on Grounds of Functionality and Failure To Function

- Citable No. 31: TTAB Sustains Opposition to Two Product Design Marks as Functional and Non-Distinctive, but Dismisses Fraud Claims

Genericness:

- TTAB Reverses Refusal to Register "MILK QUALITY TEAM" on Supplemental Register

- Sidestepping American Fertility, TTAB Affirms Genericness Refusal of "WELDING, CUTTING, TOOLS & ACCESSORIES"

- "PATENTS.COM" Generic for IP Website, Says TTAB

- Divided TTAB Panel Reverses Genericness Refusal of "DIGITAL INSTRUMENTS"

Res Judicata:

Use in Commerce/Drawing/Specimen of Use:

- Citable No. 34: TTAB Affirms Refusal of Flavor as a Mark for Pills on Grounds of Functionality and Failure To Function

- Citable No. 32: TTAB Affirms PTO Rejection of Brochure as Specimen of Trademark Use

- Citable No. 26: TTAB Reverses Failure-to-Function Refusal of "INFOMINDER" Service Mark

- TTAB Okays "SWISSAIRE" Drawing But Affirms 2(e)(2) Refusal

- Citable No. 23: TTAB Affirms "Failure to Function" Refusal of "SPECTRUM" for Dimmable Pushbuttons

- Citable No. 21: TTAB Rejects Website Specimen for Genitope's "Fingerprint Man" Mark

Proposed TTAB Rule Changes:

CAFC Decisions:

- Yankees Win Again! CAFC Affirms TTAB "BABY BOMBERS" Decision

- CAFC Affirms TTAB Dismissal of "M2 COMMUNICATIONS" 2(d) Opposition

- CAFC Affirms TTAB Rejection of Res Judicata Claim in "THINKSHARP" Opposition

- In a Non-Precedential Ruling, CAFC Affirms TTAB's Uncitable "TORRE MUGA" Decision

- CAFC Refuses Rehearing Requests in Lawman Armor Design Patent Appeal

Leo Stoller:

- The TTABlog Presents: The Leo Stoller Collection

- Leo Stoller Extension Requests Halted on April 13th

- Leo Stoller Joins the Blogosphere!

- Leo Stoller Opposes "GOOGLE" Application on Multiple Grounds

- TTAB Denies Motion to Revoke Stoller Extension of Time

- TTABlog Reply to Leo Stoller Statement of March 27th

Recommended Reading:

- TTABlog Recommended Reading: a New TMR Article on Fraud

- More TTABlog Recommended Reading: Minsker's Tips for TTAB Appeals

Other:

- Five Bloggers Kick Start ABA IPL Summer Conference

- Meet the TTABlogger at ABA 2006 Summer IPL Conference June 21 in Boston

- PLI Outline on TTAB Practice (2006?)

- From the TTABlog Songbook: "T-T-A-B"

- CAFC Refuses Rehearing Requests in Lawman Armor Design Patent Appeal

- Massachusetts Federal Court Deems "WOOLFELT" Generic for Wool Felt

- TTABlog Comment: Why File a Section 15 Declaration?

- TTABlog Posts Two "MEET THE BLOGGERS" Photos

- "Meet the Bloggers" Caps Off Tuesday Night at INTA 2006

- Thousands Descend on Toronto for INTA 2006

- Current Roster of TTAB Administrative Trademark Judges

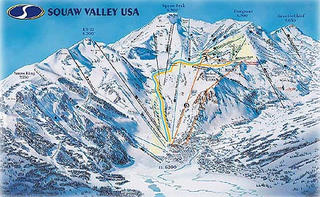

- TTABlog Flotsam and Jetsam - Issue No. 10

- "Meet The Bloggers" Event Set for Tuesday Night at INTA Toronto

- PTO Sued Over "THE LAST BEST PLACE" Cancellations and Suspensions

- TTABlog Cited in Columbia Law Review Note on Self-Disparaging Trademarks

- Will the TTAB Make All Decisions Citable?

- USPTO Seeks Nominations to Public Advisory Committees

Text and photographs ©John L. Welch 2005-2006.