In a Citable Decision, TTAB Allows Addition of Fraud Counterclaims Based on Evidence Uncovered During Testimony Period

In its fourteenth citable decision of 2005, the Board granted an Applicant's motion to add counterclaims seeking cancellation of five asserted registrations, on the ground of fraud. Although the case was already in Opposer's testimony period, the Board found the motion timely because it was based on evidence that was not previously available to Applicant. Turbo Sportswear, Inc. v. Marmot Mountain Ltd., 77 USPQ2d 1152 (TTAB 2005).

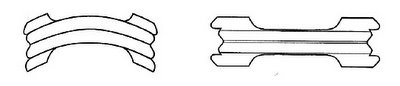

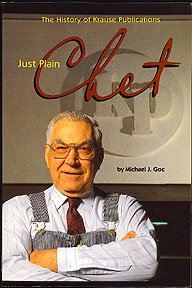

Applicant Marmot seeks to register the two design marks shown above for various goods in classes 18 and 25. Opposer Turbo claimed likelihood of confusion vis-a-vis its design mark show below, the subject of seven registrations covering various clothing items.

Applicant Marmot seeks to register the two design marks shown above for various goods in classes 18 and 25. Opposer Turbo claimed likelihood of confusion vis-a-vis its design mark show below, the subject of seven registrations covering various clothing items. On May 31, 2005, Marmot filed a motion to amend its answer in both oppositions to add counterclaims to cancel five of opposer's pleaded registrations, alleging fraud in obtaining or maintaining the registrations. Turbo then moved to amend two of its registrations to delete certain goods.

On May 31, 2005, Marmot filed a motion to amend its answer in both oppositions to add counterclaims to cancel five of opposer's pleaded registrations, alleging fraud in obtaining or maintaining the registrations. Turbo then moved to amend two of its registrations to delete certain goods.Marmot asserted that it learned during the April 27, 2005 testimony deposition of Turbo's vice-president that, for example, Turbo's mark was never used on "suits" and "sports jackets," although those goods are included in one of Turbo's registrations. It similarly learned the same regarding goods included in the other four registrations.

Turbo contended that Marmot's motion was untimely because it came during Turbo's testimony period, even though Marmot "was aware of what goods the marks were being used on when it received opposer's responses to its interrogatories in 2003."

The Board noted that counterclaims must be included in a defendant's answer, or brought promptly after the grounds therefor are learned. It concluded that the vice-president's testimony provided "information that may be relevant to each of the five registrations, and ... such information was not previously available to applicant." Turbo's interrogatory answers "dealt only with whether the marks were in use on the goods at the time the responses were provided," and "would not have apprised applicant that the marks were not in use on all of the goods at the times the applications for registration were filed, ... or at the times the Section 8 affidavits were subsequently filed."

The Board next determined that the proposed counterclaims would not be "futile," noting that under Medinol Ltd. v. Neuro Vasx Inc., 67 USPQ2d 1205 (TTAB 2003), false statements regarding use of a mark may give rise to a valid fraud claim. As to Turbo's proposed deletion of the offending goods, the Board observed that:

"Fraud cannot be cured merely by deleting from the registration those goods on which the mark was not used at the time of the signing of a use-based application or a Section 8 affidavit."

The Board issued an Order re-opening discovery and re-setting trial dates.

TTABlog comment: It remains to be seen what the Board will do with an application or registration as to which the owner has deleted certain goods before an inter partes proceeding is commenced. If an owner of a registration learns that it mark has not been used for some of the identified goods, is it sufficient to amend the registration? Will the registration, if later involved in a proceeding, survive a fraud attack? Is the best course to file a new application and abandon the possibly defective registration?

Text Copyright John L. Welch 2005