In "

Qualitex Revisited," 94

Trademark Reporter 1017 (September-October 2004), Christopher C. Larkin traces the curious transformation of the Supreme Court's decision in

Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products, Inc., 514 U.S. 159, 34 USPQ2d 1161 (1995), from a narrow ruling on whether color alone can serve as a trademark, to an important and unanticipated foundation for subsequent Court decisions on distinctiveness (

Wal-Mart) and functionality (

TrafFix).

At issue in

Qualitex was the green-gold color of certain dry cleaning press-pads. Qualitex Company had been selling green-gold press pads for more than 30 years when it sued Jacobson Products for infringement of its color trademark, registered under Section 2(f). The Supreme Court took the case in order to resolve a split in the circuits, and it ruled that color alone could be registered and protected as a trademark.

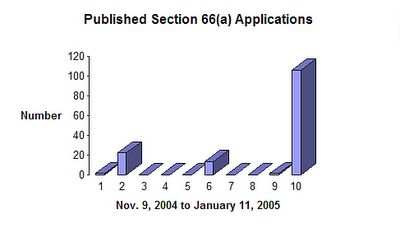

Larkin observes that the practical impact of

Qualitex on color marks has not been great. Reviewing post-

Qualitex color decisions and registration activity, he concludes that "while the decision clarified the requirements for the protection and registration of single colors as marks, it did not relax them significantly or otherwise incentivize numerous would-be registrants to seek to appropriate single colors as marks."

Larkin finds it ironic that

Qualitex is now more likely remembered for two issues that were only tangentially addressed by the Court and were not the basis for its decision.

In

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc., 529 U.S. 205, 54 USPQ2d 1065 (2000), the Court cited

Qualitex for the proposition that "“with respect to at least one category of marks -- colors -- we have held that no mark can ever be inherently distinctive." 529 U.S. at 211, citing

Qualitex, 159 U.S. at 162-163. The Court then ruled that product configuration trade dress is another category that can never be inherently distinctive. Larkin notes, however, that the existence of secondary meaning was not in dispute in

Qualitex, and thus any observations therein regarding inherent distinctiveness were arguably

dicta. Nonetheless,

Qualitex and

Wal-Mart are now cited for the rule that a single color cannot be an inherently distinctive trademark.

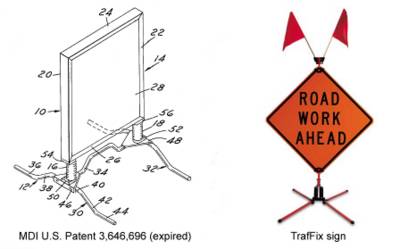

More troubling to Larkin is the Court's citation of

Qualitex in

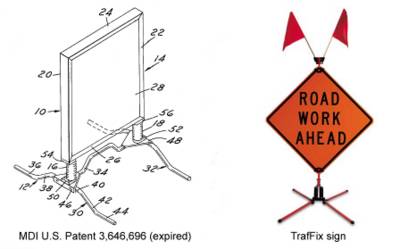

TrafFix Devices Inc. v. Marketing Displays Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 58 USPQ2d 1001 (2001), for the position that the doctrine of functionality is applied differently depending on whether

utilitarian or

aesthetic functionality is at issue.

TrafFix involved straightforward utilitarian functionality -- particularly, the effect of an expired utility patent on the trade dress protectability of a display sign. In order to draw a distinction between the two types of functionality, the Court referred to

Qualitex as a case in which aesthetic functionality was at issue.

But as Larkin points out, aesthetic functionality was

not the question in

Qualitex, and the comments by the

Qualitex Court regarding functionality were again mere

dicta. Larkin agrees with Professor McCarthy's observation that the reference to

Qualitex in

TrafFix "further clouded and obscured the issue of whether aesthetic functionality is to be given any weight." However, Larkin notes that most courts have "rejected the doctrine of aesthetic functionality hinted at in TrafFix," at least when expressed as the idea that a purely aesthetic feature can be functional.

Larkin concludes that, fortunately, the reinterpretation of

Qualitex has had a "relatively benign" impact on the law of distinctiveness and of functionality. Nonetheless, an understanding of the role of

Qualitex is indispensable to understanding of current distinctiveness and functionality principles, and Larkin's article is a very helpful roadmap.