In what might be the Board's first trade "undress" case,

pro se Applicant Joanne Slokevage failed in her cheeky attempt to register the mark

FLASH DARE! and Design for pants, overalls, shorts, culottes, dresses, and skirts.

In re Slokevage, Serial No. 75602873 (Nov. 10, 2004) [not citable].

Slokevage described her mark as:

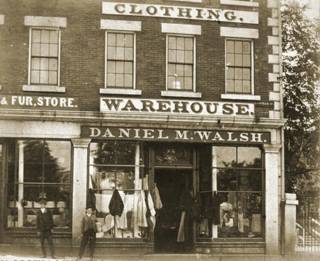

"A configuration located on the rear hips comprised of: A label in the center with the words 'FLASH DARE!' on a V-shaped background; and on each of the two sides of it there is a clothing feature (a cut-out area, or 'hole', and flap affixed to seat area with a closure device); the top borders of the 'holes' also forming and continuing the 'vee' shape. The matter shown by the dotted lines is not part of the mark, and the dotted lines serve only to show the position of the mark."

She contended that the elements of the mark, taken together, "create an edgy, eye-catching message suggesting the wearer might 'dare-to-flash' some skin on her posterior."

Ms. Slokevage declined to disclaim the design features, and she likewise declined to offer proof of acquired distinctiveness. The Examining Attorney therefore cited

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc., 529 US 205, 54 USPQ2d 1065 (2000) in refusing registration on the ground that clothing features can never be inherently distinctive.

Applicant countered that

Wal-Mart is inapplicable because her words-plus-design mark is a

unitary mark that is not subject to dissection, and that the combination of all the features provides inherent distinctiveness.

The Board, however, sided with the PTO, rejecting the argument that the subject mark is unitary: "these various elements are not so merged together that they cannot be divided and treated as separable elements." The Board also found the PTO's reliance on

Wal-Mart to be well-bottomed, agreeing that the "holes and flaps" portion of the mark constitutes a product design, which cannot be registered absent a showing of secondary meaning. Thus the Board affirmed the PTO's refusal to register on the ground that the mark "constitutes a product design which is not inherently distinctive, and would not be perceived as a trademark under Section 1, 2 and 45 of the Trademark Act."

Under Rule 2.142(g), Applicant was allowed thirty days within which to file a disclaimer of the holes and flaps portion of the mark.

Unlike many applicants seeking trademark protection for a product shape, Ms. Slokevage had already obtained a design patent for her "holes and flaps" invention:

U.S. Design Patent No. 410,689, entitled "Garment Rear." (At her website she refers to the patent as follows: "The Hole and Flap Feature is a Registered trademark, U.S. Patent No. Design 410,689.") Owners of inventive product designs typically wait until the market success of the product has been established before considering intellectual property protection. By then, it is usually too late to seek patent protection, since a patent application must be filed within one year of the first sale or offer for sale. Ms. Slokevage, however, did not make that mistake.

[My thanks to Peter Chiabotti for the link to the FLASH DARE! website, which eluded me].