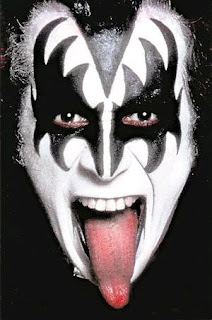

Finding that the two marks shown below, for cigarettes, falsely suggest a connection with the

Shinnecock Indian Nation, the TTAB affirmed the PTO's Section 2(a) refusals to register. The Board rejected Applicant's assertion that the PTO's refusals were based on racial discrimination against Applicant, a sole proprietorship owned by a Native American named Jonathan K. Smith.

In re Shinnecock Smoke Shop, Serial Nos. 78918061 and 78918500 (September 10, 2008) [not precedential].

Section 2(a), in pertinent part, bars registration of a mark that "may ... falsely suggest a connection with persons, living or dead, [or] institutions ...." There are four elements to such a refusal:

- (1) the mark is the same as, or a close approximation of, the name or identity previously used by another person or institution;

- (2) the mark would be recognized as such, in that it points uniquely and unmistakably to that person or institution;

- (3) the person or institution named by the mark is not connected with the activities performed by applicant under the mark; and

- (4) the fame or reputation of the person or institution is such that, when the mark is used with the applicant's goods or services, a connection with the person or institution would be presumed.

Here, the Shinnecock Indian Nation is an "institution" for purposes of Section 2(a). See

In re White, 73 USPQ2d 1713 (TTAB 2004). The Board noted that Applicant made no argument and offered no evidence regarding the four elements listed above. The Board recognized, however, that the PTO has the burden of proof, and so it proceeded with its review of the PTO's evidence.

As to the first prong of the test, the Board found that the marks consist of or comprise matter, namely the word SHINNECOCK, that is the "same as or a close approximation of" the tribe's name.

As to the second, the word SHINNECOCK would be recognized as such because it points uniquely and unmistakably to the tribe. The tribe is referred to as "the Shinnecocks" in news articles, and the record was devoid of any other meaning for the term.

As to the third, the Board found that the tribe is not connected with the activities performed by Applicant under the mark. Although Applicant is a member of the tribe, membership alone is not sufficient: "[t]here must be a specific commercial connection between applicant and the tribe, evidencing the tribe's endorsement or sponsorship of applicant's sale of cigarettes."

As to the fourth prong, "the fame and reputation of the Shinnecock tribe is such, and the nature of applicant's particular goods (cigarettes) is such, that applicant's use of its SHINNECOCK mark on cigarettes will lead purchasers to mistakenly presume that a commercial connection exists between the tribe and applicant and applicant's cigarettes." Cigarette purchasers are aware that the Shinnecocks market cigarettes, and a consumer who sees Applicant's cigarettes sold under Applicant's marks will presume the existence of a commercial connection between Applicant and the tribe. The phrase MADE UNDER SOVEREIGN AUTHORITY that appears in the marks would "reinforce and exacerbate" this mistaken presumption.

The Board thus found that all four elements of the Section 2(a) refusal had been established.

Nonetheless, Applicant contended that the PTO's refusal to register the mark was based on racial discrimination, i.e., because applicant is a Native American. He pointed to a number of existing third-party registrations owned by "non-Indians": e.g., SHINNECOCK for golf equipment; CHEROKEE for horse trailers; GERONIMO for tires; etc. Applicant argued that the only difference between this case and the issuance of the registrations is that he is a Native American.

The Board, however, even assuming that these registrations are indeed owned by non-Indians and were issued without the consent of the tribal entities named in the marks, was unpersuaded. First, it is reasonable to assume that these registrations "were issued not because the applicant's therein were non-Indians, but rather because the elements of a Section 2(a) refusal were not or could not be proven by the Office." In particular, Applicant ignored the fourth element, which requires that the mark be considered in relation to the goods. The goods of the third-party registrations, the Board noted, do not appear to be the type of goods that purchasers would associate with the named Indian tribes or personages.

Moreover, even if all the third-party registrations "were issued inappropriately and should have been refused under Section 2(a), such errors by the Office would not justify the issuance of a registration to applicant in this case," nor do they constitute a denial of Applicant's constitutional rights to due process and equal protection. Applicant's claim of racial discrimination by the Office is "unsupported by that facts" and, according to the Board, is "unavailable in any event" under

In re Boulevard Entertainment Inc., 67 USPQ2d 1475 (Fed. Cir. 2003):

"The fact that, whether because of administrative error or otherwise, some marks have been registered even though they may be in violation of the governing statutory standard does not mean that the agency must forgo applying that standard in all other cases. The TTAB's decision in this case therefore does not violate the constitutional principles that Boulevard invokes." Id. at 1480.

And so the Board affirmed the refusals to register.

Text Copyright John L. Welch 2008.