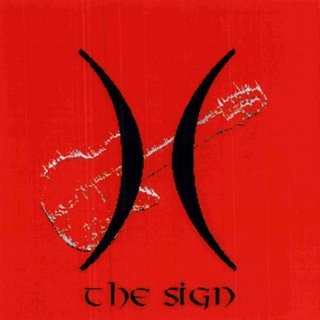

Precedential No. 6: TTAB Finds Fraud, Grants Summary Judgment in "THE SIGN" Opposition

In its sixth precedential decision of 2007, the TTAB threw out another application on the ground of fraud because the Applicants falsely claimed use of their mark in connection with all the services recited in the application. Hurley Int'l LLC v. Volta, 82 USPQ2d 1339 (TTAB 2007).

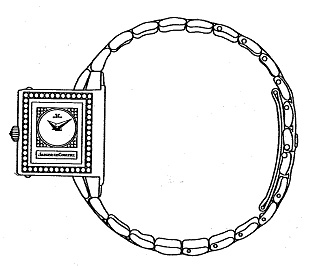

Paul and Joanne Volta, who perform as the Tasmanian musical duo "The Sign" (not to be confused with the Swedish group, Ace of Base, and their hit song, "The Sign") filed a use-based application to register the mark shown above for various entertainment services. The application stated that "Applicant is using the mark in commerce on or in connection with the ... identified goods/services." A signed declaration accompanied the application, attesting to the truth of the statements made therein.

Twice the Applicants amended the recitation of services, and twice they submitted substitute specimens accompanied by a signed declaration stating that "the substitute specimen(s) was in use in commerce as of the filing date of the application."

Opposer Hurley filed its opposition in October 2003, and then moved for summary judgment on the ground of fraud in July 2004. However, because fraud was not properly pled in the opposition, the Board denied the motion in August 2005.

In October 2005, Hurley came back with a new summary judgment motion coupled with a motion for leave to amend its notice of opposition to add a fraud claim. Applicants filed a motion for leave to amend their application.

Motion to Amend Opposition: As usual, the Board noted that leave to amend pleadings "must be freely given when justice so requires." Noting that the motion to amend was filed before the start of trial and that Applicants demonstrated no prejudice if amendment were allowed, the Board granted the motion.

Motion for Summary Judgment: Applicants admitted in their discovery responses that they had not used their mark in connection with some of the recited services. Opposer argued that this case is analogous to Medinol Ltd. v. Neuro Vasx, Inc., 67 USPQ2d 1205 (TTAB 2003) [fraud found where registrant had not used the mark on one of two goods identified], and that Applicants committed fraud on the USPTO. Opposer pointed out that Applicants reside in Australia, an English-speaking country, and that Joanne Volta apparently holds an Australian law degree. Given the "wealth of information" provided at the USPTO's website, Opposer argued, Applicants had no excuse for their false assertion.

Applicants, of course, pleaded innocence. They claimed that they misunderstood the requirements of Section 1(a), did not understand the legal meaning of "use in commerce," and "honestly believed that their ownership of the same mark in Australia and their use in commerce of such mark in Australia justified their Section 1(a) filing in the U.S." They pointed to their website, which they referred to as a "global domain." And they contended that this case is distinguishable from Medinol because they have yet to obtain a registration. Finally, they noted that Applicant Paul Volta "suffered a major coronary infarct" in November 2003, which distracted Applicants, and further that they have been "defending themselves and have no legal representation as such."

The Board was totally unsympathetic to the Applicants' plight, and it agreed with Opposer that "this case is similar to the Medinol case." The Board observed that here, as there, the application would have been refused but for "applicants' misrepresentation regarding their use of the mark on all the recited services in the application." And it is irrelevant that a registration has not yet issued.

"Applicants have provided no compelling argument why the law allows for cancellation of a registration after it is obtained through fraud, but does not allow for the prevention of a registration when fraud is revealed and the issuance of a registration is imminent."

[Significantly, the Board noted that "a misstatement in an application as to the goods or services on which a mark has been used does not rise to the level of fraud where an applicant amends the application prior to publication."]

The fact that Applicants allegedly misunderstood "a clear and unambiguous requirement for an application based on use, were not represented by legal counsel, and were suffering health problems" did not change the Board's mind. "[P]roof of specific intent is not required."

Applicants were "under an obligation to investigate thoroughly the validity of such a belief before signing their application under certain penalties." Moreover, their "asserted misunderstanding regarding the meaning of 'use in commerce' was not reasonable."

"At the time they filed their application, they knew they were seeking a registration for their mark in the United States. It was unreasonable for them to believe, however 'honest' such a belief, that the term 'use in commerce' on a trademark application in the United States meant anything other than use of the mark in commerce in or with the United States, or even that use in commerce in Australia was the legal equivalent of use in commerce in the United States."

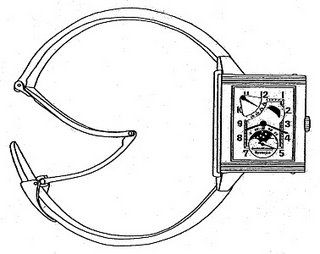

Applicants also committed fraud by submitting a supposed specimen of use that they knew had not been used in U.S. commerce. In fact, Applicants admitted in discovery that "the Kaos Cafe, the location indicated in the advertisement flyer submitted as a substitute specimen, is located in Australia."

The Board therefore deemed the application void ab initio and entered summary judgment in Opposer's favor.

Applicant's Motion to Amend Application: Applicants sought to amend their filing basis to Section 44(e). However, the Board observed that "the proposed amendment does not serve to cure a fraud that was committed." Therefore, it deemed this motion "moot." [The Board noted, however, that its decision here does not preclude Applicants from filing a new Section 44(e) application].

TTABlog comment: Well, at least the Board is making its position on fraud very clear. False statements of fact regarding use of a mark are fatal to an application, unless corrected prior to publication of the application for opposition. After publication, fuggedaboudit. Whether the applicant is foreign or pro se (or both), it doesn't matter. The application is doomed.

Are there still some gray areas? Yes. For example: last year's Maids to Order case (TTABlogged here), where the question was whether, under the particular facts, Respondent's mark had been used in interstate commerce or just intrastate commerce. But in the instant case, the question wasn't even close.

Practitioners would be wise to review their pending applications to make sure that all allegations of use are correct. There is still time to correct erroneous claims prior to publication of the application, and thereby avoid fraud. Perhaps receipt of an Approval for Publication should be a trigger for a review of the application's use allegations.

For a discussion of other recent TTAB fraud cases, see the TTABlog Fraud Collection (here). Also see last year's Trademark Reporter article by Karen P. Severson, entitled "Filer Beware: Medinol Standard Set Forth by the United States Patent and Trademark Office," 96 Trademark Reporter 758 (May-June 2006).

Text Copyright John L. Welch 2007