Bizarre Appeal Charges TTAB With Destroying Al Qaeda-Related Evidence

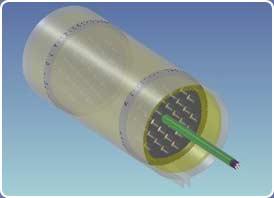

In one of the strangest TTAB cases in years, Jet Airways, Inc. of Bethesda, Maryland, has appealed to the CAFC from a TTAB interlocutory order striking the company's "Response" to a Petition for Cancellation filed by an Indian company, Jet Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. The Petitioner seeks to cancel on Section 2(d) grounds, U.S. Registration No. 2,839,676 for the mark JET AIRWAYS & Design (shown immediately below) for various air transportation services ("JET AIRWAYS" disclaimed). (Cancellation No. 92044201).

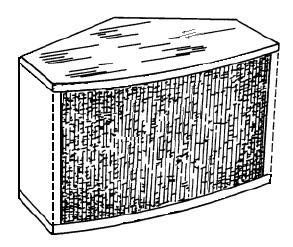

Petitioner's own applications to register the mark JET AIRWAYS THE JOY OF FLYING & Design ("JET AIRWAYS" disclaimed) have been blocked by the challenged registration, leading to the filing of the cancellation petition, in which Petitioner alleged priority of use and likelihood of confusion.

Petitioner's own applications to register the mark JET AIRWAYS THE JOY OF FLYING & Design ("JET AIRWAYS" disclaimed) have been blocked by the challenged registration, leading to the filing of the cancellation petition, in which Petitioner alleged priority of use and likelihood of confusion.

Registrant, in its 25-page pro se "Response," ignored the specific allegations of the Petition To Cancel, and instead asserted, inter alia, that the petition:

"is an attempt by a terrorist group to gain a foothold into the United States by obtaining permission to operate an international airlines which can fly in to the United States for evil intentions through the issuance of a trademark. Petitioner Jet Airways (India) Ltd. will become a commuter airline for Al Qaeda if granted the Registrant's JET AIRWAYS trademark and landing rights." (page 24).

Petitioner moved to strike the "Response" on the ground that it failed to properly address the allegations of the Petition To Cancel, contained irrelevant and impertinent matter, and failed to comply with the Rules of Procedure. The Board, through the assigned Interlocutory Attorney, agreed. On June 23, 2005, it issued an Order striking the "Response" and allowing Registrant 30 days to file "an amended answer that conforms" with the applicable rules. The Interlocutory Attorney also gave Registrant some advice:

"The Board notes that in its original answer, respondent raises numerous assertions that fall outside the Board's narrow jurisdiction. Respondent is advised that the Board will not consider any allegations touching on matters not within our jurisdiction." (page 5).

On July 7, 2005, Jet Airways, Inc. filed a lengthy Notice of Appeal from the Board's Order (docketed July 19, 2005 as CAFC Appeal No. 05-1473), alleging that the Order violated various federal laws and denied "her" (i.e., Nancy M. Heckerman, Appellant's president) constitutional rights by "removing, mutilating, obliterating, or destroying all pleadings and evidence contained in" its Response, evidence "which proved that the Petitioner in this cause, Jet Enterprises Pvt. Ltd., was, and still is, directly and indirectly linked to Al Qaeda, a known Enemy of the United States." (pages 3-4). It also asserts that "a great amount of injury will be released upon the United States by the Petitioner Jet Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. if it is allowed to steal the Appellant's American Registered trademark in order to enter the U.S. and operate its Al Qaeda jihad airline." (page 4).

According to Appellant, by destroying these documents the "officers of the TTAB have violated their Oath of Office and thus, the Constitution of the United States, to support a known terrorist organization," and have committed "treason against the United States." (pages 4, 12).

The Board has now suspended the cancellation proceeding pending the outcome of the CAFC appeal.

TTABlog comments: At the heart of the CAFC appeal is Appellant's erroneous belief that, because the TTAB granted the motion to strike the Response to the Petition to Cancel, the documents that comprised the response were actually destroyed. In fact, the Response (including the exhibits) is publicly available for viewing and downloading at the TTABVUE website. For that reason alone, the appeal seems doomed.

Apparently the boundaries of this controversy are not limited to the TTAB. A press release available at Petitioner's website states that "Ms. Nancy Heckerman had made scandalous, scurrilous and baseless allegations regarding alleged links of Jet Airways (India) Limited with undesirables in a letter of objection to the US Department of Transportation," and that the Indian company has engaged the services of a leading American law firm "to initiate legal charges against the President & CEO, Ms. Nancy Heckerman of Jet Airways Inc."

TTABlog update: The appeal to the CAFC was dismissed on February 10, 2006, without opinion.

Text Copyright John L. Welch 2005.