TTAB Affirms 2(a) Disparagement Refusal of STOP THE ISLAMISATION OF AMERICA

The Board affirmed a Section 2(a) refusal to register the mark STOP THE ISLAMISATION OF AMERICA for "providing information regarding understanding and preventing terrorism," finding the mark to be disparaging to Muslims in the United States. Even if, as Applicants argued, "islamization" refers to a non-violent "political movement to replace man-made laws with the religious laws of Islam," the use of Applicants' mark in connection with services that provide information regarding "understanding and preventing terrorism" would be disparaging to a substantial composite of Muslims. In re Pamela Geller and Robert B. Spencer, Serial No. 77940879 (February 7, 2013) [not precedential].

The test for disparagement of a non-commercial group, such as a religious or racial group, is as follows:

1. What is the likely meaning of the matter in question, taking into account not only dictionary definitions, but also the relationship of the matter to the other elements in the mark, the nature of the goods or services, and the manner in which the mark is used in the marketplace in connection with the goods and services; and

2. if that meaning is found to refer to identifiable persons, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, whether that meaning may be disparaging to a substantial composite of the referenced group.

Meaning of the mark: Based on dictionary definitions provided by Examining Attorney Maria-Victoria Suarez, considered in the context of Applicants' services, the Board found that the subject mark connotes that "conversion or conformance to Islam must be stopped in order to prevent the intimidating threats and violence associated with terrorism." Articles posted at Applicants' website urged that the "spread of Islam in America is undesirable and must be stopped." Comments to Applicants' blog "reflect the website's message of stopping the spread of Islam in the United States." All of this evidence supported the meaning of the mark proposed by the Examining Attorney: "to stop the conversion or conformance to Islam in America in order to avoid terrorism."

Applicants contended that Muslims understand "Islamisation" to mean "the term of art to incorporate the political-legal movement to convert a society or politic into a political society predicated upon and governed by Islamic law (i.e., Shariah)." In support, Applicants pointed to use of the term by professionals, academics, and religious and legal experts.

The Board, however, agreed with the Examining Attorney that the definitions from several online dictionaries are more reflective of the public's current understanding of the term "Islamisation." It concluded that one meaning of the mark is the one proposed by the Examining Attorney, but the mark has a second meaning, as espoused by Applicants, to the narrower group that Applicants cited.

The Board noted that when a term has two meanings, both meanings advance to the "second phase" of the analysis: does the relevant group consider the term, as used in the context of the services, to be disparaging?

Disparaging or not? Applicants argued that if the word "Islamisation" refers only to those groups and movements that seek to compel a change of the political order to adopt Islamic law as the law of the land, then "law abiding and patriotic Muslims, who are not members of such groups, would not be disparaged by the mark." The Board found two problems with that argument: it assumes that a substantial composite of Muslims embraces the meaning of "Islamisation" that Applicant espouses, and that they would not be offended by Applicants' mark.

However, there was no evidence that a substantial composite of Muslims understand "Islamisation" to have the meaning that Applicants' assert. The narrow evidence submitted by Applicants did not show how the term is perceived by the general Muslim population of the United States.

The Board observed that, even if a substantial composite of Muslims embraced the more specific meaning offered by Applicants, the mark is disparaging "because the term 'Islamisation' has another more general meaning relating to conversion to Islam." If the general, non-Muslim population understands the term to refer to converting or conforming to Islam, and adopts the more likely meaning of "stopping the spread of Islam in America," a substantial composite of Muslims (regardless of their understanding of the meaning of the term) would be disparaged by the mark.

The admonition in the mark to STOP sets a negative tone and signals that Islamization is undesirable and is something that must be brought to an end in America. In light of the meaning of “Islamization” as referring to conversion to Islam, i.e., spreading of Islam, use of the mark in connection with preventing terrorism creates a direct association of Islam and its followers with terrorism.

In sum, the Board found "sufficient evidence that the majority of Muslims are not terrorists and are offended by being associated as such." Consequently, the use of applicants’ mark in connection with the recited services would be disparaging to a substantial composite of Muslims in America.

The Board also found the mark disparaging under applicants’ definition of “Islamisation” as a political movement to replace man-made law with the religious laws of Islam. A "further flaw" in applicants’ argument is that it ignores the nature of the services identified in the subject application.

In view of the foregoing, we find that under either meaning of applicants’ mark, when the mark is used in connection with the services identified in the application, namely providing information for understanding and preventing terrorism, the mark is disparaging to Muslims in the United States and is therefore not registrable.

Freedom of speech: Finally, applicants argued that the refusal to register violated their First Amendment right to freedom of speech. The Board, however, observed that its decision affects only the right to register the subject mark and does not impede their right to use the mark. "[I]t imposes no restraint or limit on their ability to communicate ideas or express points of view, and does not suppress any tangible form of expression."

Read comments and post your comment here.

TTABlog comment: What about a mere descriptiveness refusal?

Text Copyright John L. Welch 2013.

8 Comments:

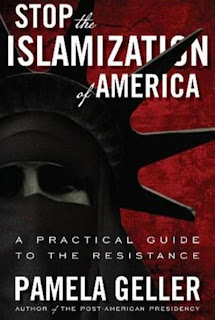

In my opinion, the specimen shows the mark being used as a title of a book. Since titles are not trademarks unless it is used for a series, would a rejection be based on that the specimen does not show use of the mark as a trademark?

Her arguments regarding the political purpose behind her message reinforces my view that she isn't really using the phrase as a trademark, or that it's just descriptive with no secondary meaning.

Actually, this is an intent-to-use application. The picture is not the specimen of use.

I was going to comment that her "mark" seemed to be descriptive of her services. But I forgot. Thanks for doing so.

The Board is using Sec. 2(a) to enforce political correctness, which has never been part of trademark law.

Rob - I don't think this has anything to do with political corectness. The fact is that muslims will find this purported trademark offensive. As such, it is subject to an absolute bar under Section 2(a). That's what the law says. Your right to free speech under the First Amendment does not entitle you to a grant of TM rights under the Lanham Act.

Orrin,

You wrote: "The fact is that muslims will find this purported trademark offensive."

It's not a fact, but an ideology-turned-fact based exclusively on PC-derived assumptions that are not in evidence. Some Muslims may oppose Islamization of the country, just like not all Christians wish to make this country Christian. There are still people of all religions in support of the separation of church and state.

To clarify, my first comment wasn't about the first amendment, but about the Board's blatant injection of PC ideology to trademark law.

It seems problematic to refuse registration under disparagement as it assumes facts not in evidence. Besides, isn't descriptiveness a perfectly adequate as well as more appropriate ground for refusal?

Post a Comment

<< Home