TTAB Reverses "ANDIAMO" 2(d) Refusal: Insufficient Proof that Wine and Restaurant Services are Related

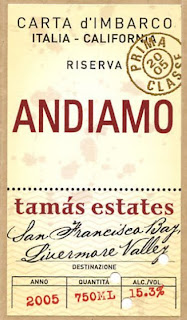

Reversing a Section 2(d) refusal to register the mark ANDIAMO for wine, the Board found the mark not likely to cause confusion with the identical mark registered for restaurant services. The law requires "something more than that similar or even identical marks are used for food products and for restaurant services." Here, the "something more" was lacking. In re Wente Bros. dba Tamas Estates, Serial No. 77314718 (August 6, 2009) [not precedential].

The CCPA's decision in Jacobs v. International Multifoods Corp., 212 USPQ 641 (CCPA 1982), set forth the "something more" requirement.

The Examining Attorney contended that restaurants commonly serve wine and that wineries commonly feature restaurants (as does Applicant's winery). Applicant pointed out the lack of evidence that "it is common in the industry for restaurants to offer and sell private label wine named after the restaurant or that either party's wines are served in the other's restaurants."

The Board reviewed the "something more" cases, noting that the requirement has been met in various ways but that "the facts in this case are much less persuasive."

The only evidence of record to show that the goods are related is the simple picture of a bottle of wine along with other food items in a flyer about registrant's takeout services and the fact that applicant has a restaurant with a different name at its winery. We find that this evidence is not enough to show the "something more" required by Jacobs.

The Board recognized that some consumers may patronize the ANDIAMO restaurant and then may go to applicant's winery and eat at The Restaurant at Wente Vineyards. They may order a bottle of ANDIAMO wine and believe that the sources of the wine and the restaurant services are related. However, the Trademark Act requires likelihood of confusion, not the mere possibility of confusion. The CAFC's Coors Brewing decision requires significant evidence of relatedness:

It is not unusual for restaurants to be identified with particular food or beverage items that are produced by the same entity that provides the restaurant services or are sold by the same entity under a private label. Thus, for example, some restaurants sell their own private label ice cream, while others sell their own private label coffee. But that does not mean that any time a brand of ice cream or coffee has a trademark that is similar to the registered trademark of some restaurant, consumers are likely to assume that the coffee or ice cream is associated with that restaurant. The Jacobs case stands for the contrary proposition, and in light of the very large number of restaurants in this country and the great variety in the names associated with those restaurants, the potential consequences of adopting such a principle would be to limit dramatically the number of marks that could be used by producers of foods and beverages.

And so the Board reversed the refusal to register.

TTABlog comment: I don't have a quibble with the outcome here, but it's worth pointing out that these food/restaurant "something more" cases are all over the lot. Check out this one and this one, by way of example.

Text Copyright John L. Welch 2009.

2 Comments:

John:

The lack of clarity over the "something more" requirement has been a pain in the neck for folks in the wine industry. It seems that Examining Attorneys routinely reject applications using the analysis that the Board rejected in Andiamo and it takes a great deal of convincing to get them to apply the Coors Brewing standard. Perhaps this decision will help reduce the amount of reflexive office actions.

Paul

Indeed, this case appears to be at odds with In re Constellation Wines U.S., Serial No. 78803750 (April 17, 2008), wherein the TTAB found the complete opposite, i.e., that there is a close relatedness of wine to restaurant services. Perhaps, in the present case, the TTAB did not find like it did in In re Constellation, because in the present case the mark ANDIAMO was not found to be a strong mark; or perhaps, because the record in the present matter is factually poor. The moral of the story: since trademarks are decided on a case by case basis, on the basis of the record, beef up the record with facts that support your position. Don’t just rely on case law. That’s why the Davey case discussed below is so great.

Post a Comment

<< Home