"NO FRIGGIN CLUE" Confusingly Similar to "CLUE" for Video Games, Says TTAB

The Board sustained Hasbro's opposition to registration of the mark NO FRIGGIN CLUE for, inter alia, computer and video games, finding it likely to cause confusion with the "well-known and strong" mark CLUE registered for board games and computer and video games. The Board recognized that the marks are "somewhat, but not strongly, similar" and admitted that this is a "close case," but it resolved any doubt in favor of the prior registrant. Hasbro, Inc. v. Braintrust Games, Inc., Opposition No. 91169603 (August 24, 2009) [not precedential].

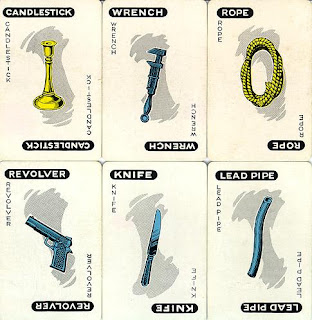

Hasbro argued that its CLUE mark is famous, based on its history and length of use (60 years), the marketing of CLUE-branded products, and the success of the brand in the marketplace. In addition to the classic board game, Hasbro has licensed use of the mark for a number of variations of the game, and has published the game in a number of electronic formats. Both a movie and a Broadway show have been produced under license, as have ancillary goods such as greeting cards, clothing, and casino games.

Applicant successfully argued that Hasbro failed to explain the significance of its sales and advertising figures or how these figure "measure up to its competitor's figures." The Board pointed out that, in view of the "extreme deference that is accorded to a famous mark," one who claims its mark is famous "must clearly prove it." Hasbro failed to carry that burden. However, the Board found that the mark CLUE is "a well-known and strong mark, and enjoys considerable renown." This factor "significantly supports a finding of likelihood of confusion, and entitles the mark to an enhanced scope of protection."

As to the goods, Applicant argued that its games are "trivia-related," whereas the CLUE games are not. The Board pointed out, however, that there was no such restriction in the opposed application or in the CLUE registrations, and the Board's Section 2(d) determination is based on the identification set forth in the application and registrations, "regardless of what the record may reveal as to the actual nature of the goods."

The Board found the goods of the parties to be in part identical (e.g., "video game software") and in part closely related, a factor that "strongly supports a finding of likelihood of confusion." Likewise, the overlapping goods are presumed to travel in the same channels of trade to the same classes of purchasers.

Turning to the marks, the Board observed once again that, when the goods are identical, a lesser degree of similarity between the marks is necessary to support a finding of likely confusion. The Board found that the term CLUE has the same connotation in each mark:

With respect to games in general and both applicant’s and opposer’s games in particular, a “clue” is something which points the way to the correct answer. In the case of applicant’s game, that would be the correct answer to the trivia question at hand. In the case of opposer’s games, a “clue” is an aid to solving the mystery at hand. In other words, the term CLUE and its concept are central to both of the parties’ goods. Here, while both parties’ use of the term CLUE is somewhat suggestive, both marks use the term to suggest the same thing.

The Board pointed out that Applicant's mark incorporates Hasbro's mark in its entirety, and it concluded that "this similarity would not be lost on consumers viewing the respective marks on identical goods ..., particularly in light of the renown of opposer's mark."

While the marks are clearly not identical, we find that applicant’s mark and opposer’s mark are similar in appearance and sound to the extent that they both comprise the term CLUE. This factor lends some support to a finding of likelihood of confusion.

The Board pooh-poohed Applicant's feeble third-party registration evidence and its "lack-of-actual-confusion" argument.

Concluding that, on balance, confusion is likely, the Board observed that "[t]his is admittedly a close case. Nonetheless, to the extent we have any doubt, we must resolve that doubt in favor of opposer, the prior registrant."

Tip From the TTABlog: It pays to spend the time and effort to prove that your mark is strong. The stronger the mark, the broader the protection. I don't agree that the marks here are sufficiently similar, and I would have ruled in favor of Applicant. But the key to Hasbro's win was the strength of its mark.

Text Copyright John L. Welch 2009.

2 Comments:

I'd say that in this case it was the TTAB that had "No Friggin Clue." Seriously, do the people at the TTAB really think that it is more likely than not that consumers would think that Hasbro would make a game called "No Friggin Clue"? Bad decisions like this hapen when you can't prove dilution.

I agree, "No Friggin Clue" has a completely different connotation.

Post a Comment

<< Home