CAFC Clarifies duPont Fame Test In Affirming TTAB's "VEUVE ROYALE" Decision

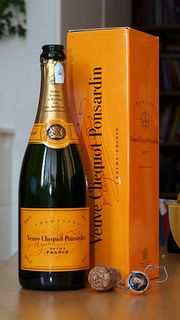

Ruling that fame for likelihood of confusion purposes is to be measured with regard to "the class of customers and potential customers of a product or service, and not the general public," the CAFC affirmed the TTAB's August 4, 2003 decision refusing registration of the mark VEUVE ROYALE for sparkling wine. The Board had found the mark likely to cause confusion with Opposer's trademark and trade name VEUVE CLICQUOT, and its registered marks VEUVE CLICQUOT PONSARDIN for champagne wines and THE WIDOW for wines. In its precedential ruling, the CAFC agreed vis-a-vis the first two marks, but reversed the Board's conclusion as to the third mark. Palm Bay Imports, Inc. v. Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin Maison Fondee En 1772, 73 USPQ2d 1689 (Fed. Cir. 2005).

The CAFC first considered Opposer's two VEUVE marks:

Applicant Palm Bay contended that the Board was wrong in it findings on four of the duPont likelihoood of confusion factors: the similarity of the marks; third-party use of the term VEUVE; the fame of Opposer's marks; and the sophistication of purchasers.

As to the marks, the CAFC noted that the Board made a "minor misstatement" regarding the test for similarity "in an otherwise proper analysis." The Board treated "commercial impression" as the ultimate conclusion, rather than as a separate factor to be considered with appearance, sound, and meaning. But that was not reversible error. As to the relative importance of the words VEUVE and CLICQUOT, the Board correctly concluded that VEUVE is "prominent in the commercial impression" created by Opposer's mark, and "the dominant feature" in Palm Bay's mark. "The presence of this strong distinctive term as the first word in both parties' marks renders the marks similar, especially in light of the largely laudatory (and hence non-source identifying) significance of the word ROYALE.

Palm Bay next argued that the Board erred in rejecting evidence of five different third-party uses of VEUVE for alcoholic beverages. The CAFC, however, pointed out that most of Palm Bay's evidence -- listings in industry directories -- was not evidence of the consuming public's awareness of these marks. As to its marketing evidence regarding one of the third-party users, that evidence "does not rise to the level of demonstrating that the single third-party use was so widespread as to 'condition' the consuming public" to distinguish between different VEUVE marks.

As to the Board's finding of fame, Palm Bay asserted that the Board was incorrect in measuring fame with regard to a narrow class of purchasers rather than the general public. The CAFC noted that prior fame cases had not directly addressed this issue, and it agreed with the Board by holding:

"the proper legal standard for evaluating the fame of a mark under the fifth duPont factor is the class of customers and potential customers of a product or services, and not the general public."

Considering Opposer's proofs -- substantial sales and advertising expenditures since 1980, ranking as the second leading champagne brand in this country, widespread media exposure, an admission of fame by Palm Bay's President, and several WIPO domain name decisions finding the marks to be famous -- the CAFC ruled that "substantial evidence supports the Board's finding of fame."

Finally, as to the sophistication of consumers, the Board did not err in holding that this factor was "neutral, at best." The CAFC agreed that "champagne and sparkling wines are not necessarily expensive goods which are always purchased by sophisticated purchasers who exercise a great deal of care in their purchases." And even sophisticated consumers could conclude that VEUVE ROYALE was Opposer's sparkling wine.

Turning to Opposer's mark THE WIDOW, the Board had found similarity in part under the doctrine of foreign equivalents, because "an appreciable number of purchasers in the U.S. speak and/or understand French, and they 'will translate' applicant's mark as 'Royal Widow.'" [This was inconsistent with the Board's assertion, when comparing Opposer's VEUVE marks with Palm Bay's mark, that purchasers are not likely to translate VEUVE into "widow."] The CAFC observed that the doctrine of foreign equivalents should be applied only when it is likely that the "ordinary American purchaser would 'stop and translate [the word] into its English equivalent.'" It found that substantial evidence did not support the Board's finding on this issue, and it therefore reversed as to the mark THE WIDOW.

The TTABlog notes particulary the CAFC's comments regarding the relevance of WIPO domain name arbitration decisions that had found Opposer's marks to be famous. Although WIPO examined fame on a worldwide basis, rather than in the USA only, those decisions "nonetheless provided a 'confirmatory context' for [Opposer's] other evidence of fame." This is believed to be the first time the CAFC has indicated that the findings in a UDRP arbitration may have some relevance in a TTAB proceeding, and it is a ruling that is rather troublesome, since Palm Bay was not a party to the UDRP proceedings and had no opportunity to contest the finding of fame that the Board used against it.

Text ©John L. Welch 2005. All Rights Reserved.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home